Going into my fourth year as a History PhD student at Howard University, I’ve been reminded of a defining question that Stokely Carmichael once asked budding historian, Peniel Joseph: “Are you working for the liberation of your people?” While Joseph proudly nodded in affirmation before the elder activist, I have found myself struck in an existential crisis of sorts: Where does my love for historical and visual storytelling intersect with the fight for local issues, like the battle for DC Statehood? And so I embarked on a deeply personal journey to excavate Washington, DC’s past, because I want to be a citizen of its future.

This journey led me to explore a space as a paid intern that I probably would have been afraid to enter otherwise: the DC History Center. Located inside what was once Washington, DC’s first central public library, the DC History Center has shared the historic Carnegie Library with an Apple store since the building reopened in 2019 after a renovation. Notably, the Carnegie Library has always been open to students of color like me, since it opened in 1903; however, with its all-white interior, columned halls, pristine minimalistic aesthetic, ever-watchful security, and Big Tech neighbor on the main floor, it’s easy to feel intimidated by the space: Is it even meant for me? This summer showed me, emphatically, yes.

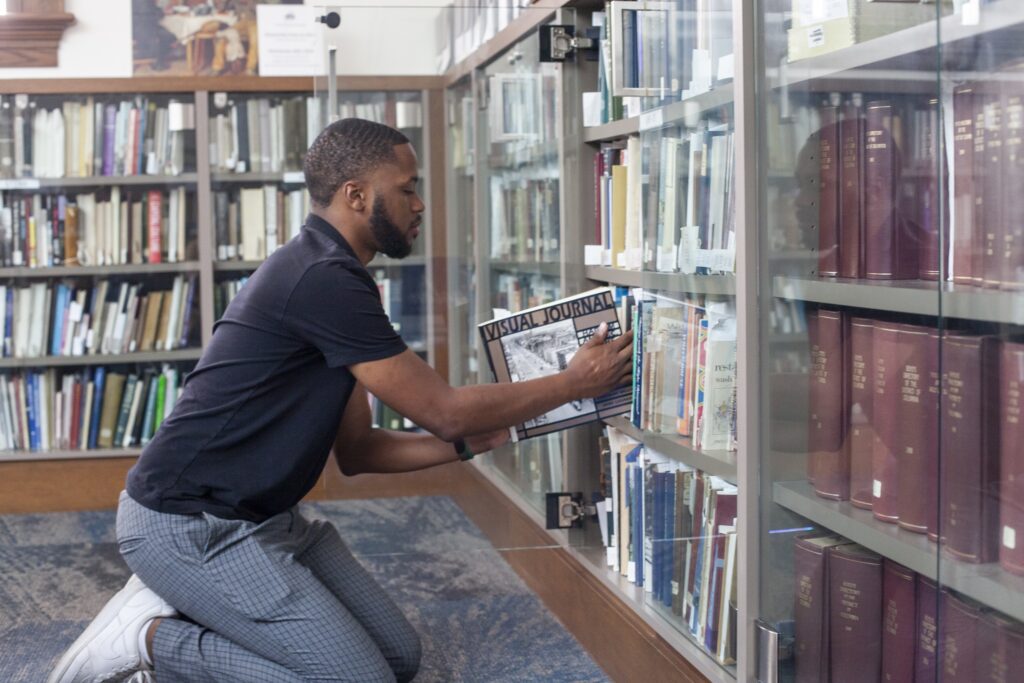

As an intern supporting the DC History Center’s K-12 education programs, including the Clarice Smith Neighborhood History Program, I was charged with selecting resources to support teachers as they guided their students in the history of DC’s neighborhoods. During my internship, I sought answers in the Kiplinger Research Library, using the DC History Center’s treasure trove of maps, photographs, books, dissertations, and a litany of other material to guide me. Alex, the librarian, and Jade, the library assistant, patiently pulled box after box of archival materials from the collection. I used these artifacts to help me understand what happened to people in marginalized communities like Southwest—people who were forcibly removed from their homes to make way for “urban renewal.” In other words, the process James Baldwin aptly called “Negro removal,” wherein the government, using the power of eminent domain, destroyed vibrant Black and immigrant urban communities to build “modern” living and shopping spaces.

During my research, I reflected on how communities that were destroyed or pushed out of this city may not have felt that their stories mattered or were worth preserving to pass on to future generations. I came to realize that these stories go beyond the traditional definition of “home” or “belonging” to a place.

I noticed I wasn’t alone in the library, and by alone, I mean I wasn’t the only person who fully embodied Chocolate City and its diverse communities. Joining me were queer researchers, Latino/a/x researchers, and others—all of us hoping to find different keys to unlocking stories that were previously hidden. Throughout this experience, the DC History Center staff actively listened to our perspectives and pointed us to collections and maps that would be meaningful on our journeys.

As I returned to my post each Tuesday and Thursday, I slowly compiled enough information to include in the DC History Center’s Teaching DC Neighborhoods guide. The hope is that local educators won’t just be able to follow in my footsteps, but they will have the agency to seek their own paths of curiosity alongside their students. Nothing could have prepared me for the very real, hands-on work that DC teachers are actively thinking through for their classrooms.

In addition to contributing to the resource guide, I supported a week-long professional development program, Teach the District. This joint program of the White House Historical Association and the DC History Center has one central goal: to encourage student civic engagement by helping K-12 teachers and librarians navigate the local history resources across the city, including the collections of the two partner organizations, the DC Public Library, the Sumner School Museum and Archives, and many more.

I entered Teach the District thinking I would excitedly tell these educators about the guides I created to excavate the diverse stories of local communities, but all of that was turned on its head the more questions I heard from our audience. I heard questions like, “How can we use these primary sources to connect with our students?” or “How can I find a map of what my students’ neighborhoods used to look like?” I began to realize that in order for students to see themselves in this story of DC liberation, their teachers needed to have a sense of place, identity formation, and how the city has changed over time. These educators, importantly, were looking to go beyond the curriculum. They wanted to do more than just reflect other scholars’ thoughts— they wanted to uncover what defines everyday Washingtonians today.

Through my work with the collections, I’ve been challenged to think more critically about how marginalized communities in DC have survived. If I’m completely honest with myself, I always thought of teaching as a traditional anti-dream. Admittedly, I had the simplistic notion that teachers had to be married to their curriculum and therefore had no room to curate original, creative lessons that emphasized local history. But by helping to run this professional development program I’ve happily witnessed that today’s teachers are doing more than simply sticking to a curriculum—they’re training the District’s youth to be active liberators of their city.

While I compiled resources for these educators to guide their way through DC’s neighborhoods, I realized that liberation begins by learning to ask critical questions of students to help them come to their own conclusions about history, based on well-informed discussions and primary material from the not-so-distant past. I thought I was teaching the District, but in fact, I have so much more to learn—about myself and this place I call home. I look forward to a life where the District will keep teaching me.

Phillip Warfield is a professional historian-in-training and digital storyteller, creating multi-platform, digital content based around his love for Black history, intercultural relationships, popular culture, and self-improvement. He is proud to be African American and is content being a nomad—he’s lived in ten different states and a dozen cities across America. He firmly believes in the necessity of contextualization and the strength of histories hidden deep within mainstream narratives.

Phillip Warfield is a professional historian-in-training and digital storyteller, creating multi-platform, digital content based around his love for Black history, intercultural relationships, popular culture, and self-improvement. He is proud to be African American and is content being a nomad—he’s lived in ten different states and a dozen cities across America. He firmly believes in the necessity of contextualization and the strength of histories hidden deep within mainstream narratives.