In this Place of Interest, DC History Center volunteer John P. Olinger looks back at the ClubHouse, a remarkable nightclub founded by Black members of DC’s LGBTQ community that filled multiple social needs from 1975 to 1990. Check out the Rainbow History Project’s short video series about the ClubHouse.

A small group of dedicated Black LGBTQ Washingtonians opened the ClubHouse to serve their community in 1975. Tucked away in a residential neighborhood in Northwest DC, over the next 15 years the ClubHouse became a nationally known after-hours dance club and a seedbed of important developments in the LGBTQ communities.

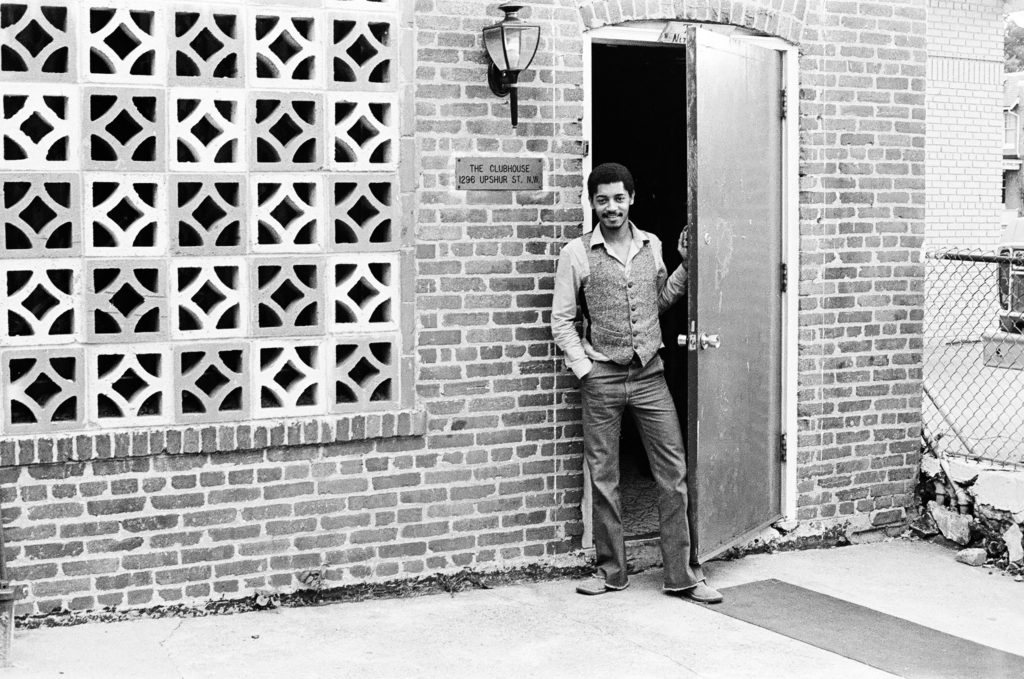

It was “a place where anyone 16 and over could go and have the house party they couldn’t have in their house,” recalled John Eddy, president and one of the founders of the ClubHouse. Eddy, Aundrea Scott, Scott’s sister Paulette, Morrell Chasten, and Rainey Cheeks opened the club at 1296 Upshur Street NW across from Theodore Roosevelt High School in Petworth in 1975.[1]

The ClubHouse’s opening night, Saturday of Mother’s Day weekend, was the end of one journey for DC’s Black LGBTQ community and the beginning of another.

In the 1960s, the Metropolitan Capitalites, a Black LGBTQ social club, organized house parties for African American gay and lesbian Washingtonians. Faced with discriminatory practices or outright rejection by the White gay community’s bars and clubs, African Americans socialized in homes, adding their own flavor to a long tradition in the larger African American community. Buddy Sutson recalled in a 2001 oral history interview with Mark Meinke of the Rainbow History Project that Washington was known for the house parties that built a tight-knit community. The Metropolitan Capitalites’ parties at Michael Burton’s house at 4011 14th Street NW were particularly popular. As the parties grew, Eddy, Chasten, and the Scotts, members of the Metropolitan Capitalites, looked for a new location. In 1969 they opened Zodiac Den in the basement of a country western bar patronized by White motorcyclists at 221 Riggs Road NE. Three years later when the upstairs bar closed for non-payment of taxes, they took over the whole building. Third World, the new entity, operated there until 1976. [2]

What was to become the ClubHouse grew out of Scott and Eddy’s experiences at the Loft in New York City. The Loft pioneered invitation-only dance parties in industrial or warehouse spaces. The founders decided to create something similar in Washington. As John Eddy said, “We wanted to give the community—total—gay as well as the straight—something different in the city, a place to come, relax, and party.” They struck gold when Eddy found 1296 Upshur Street in 1974.[3]

The space was originally built in 1930 as a garage-plus-new-car-showroom. Subsequently it housed a furniture store and then a warehouse. It was out of the way, in a residential, predominantly African American neighborhood, far from the downtown White gay life. Jay Jay Tate, one of the club’s DJs, described it as “a very non-descript building. . . . Unless someone told you exactly where it was,” you wouldn’t know the club was there.[4]

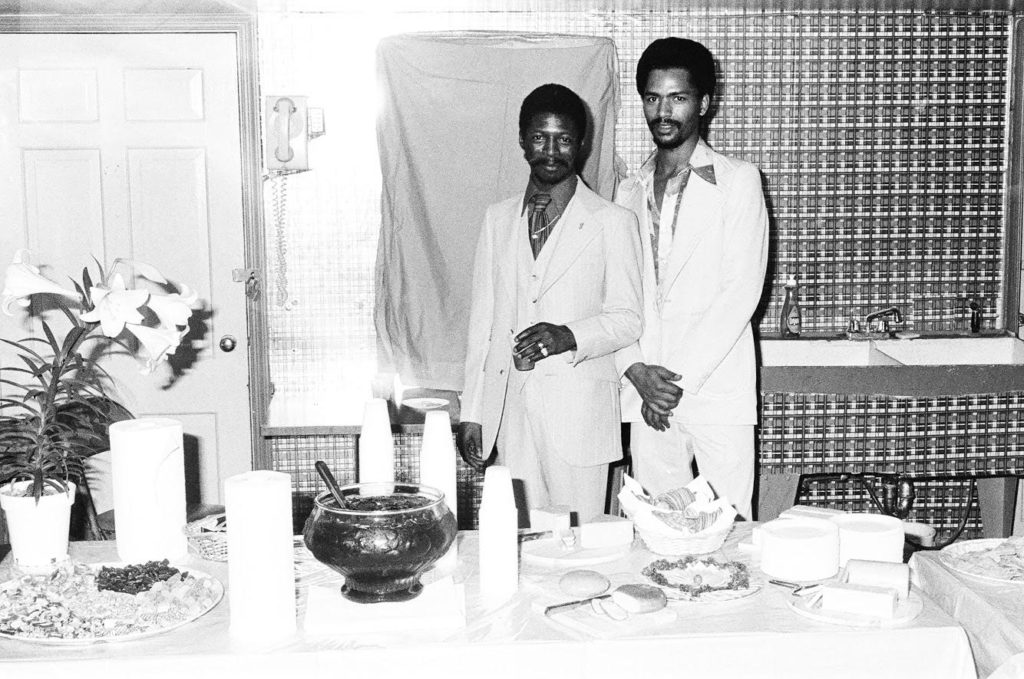

The founders signed a lease for the 10,000-square-foot warehouse. With their own money and a small bank loan, doing the work themselves, they reconfigured the space for dancing and socializing, while keeping the basic structure of what had been two conjoined buildings. As with the Loft, the ClubHouse was set up as a membership club. Membership was free, but members, often business people, retail workers, and government employees, had to subscribe to a code of conduct. Scott interviewed all prospective members. Once admitted, ClubHouse members paid a $4 admission fee at each visit. Guests paid more. By opening night the Clubhouse had enrolled 400, a number that grew over the years to 4,000.

A New Space, A New Experience

Jay Jay Tate, a club DJ, called it a safe space. Rainey Cheeks, a club manager and nationally top 10 ranked martial arts competitor, said it was created for artists. John Eddy said it was a place for everyone. It was a great place to go, party with friends, make new friends, to see, to be seen, to dance.

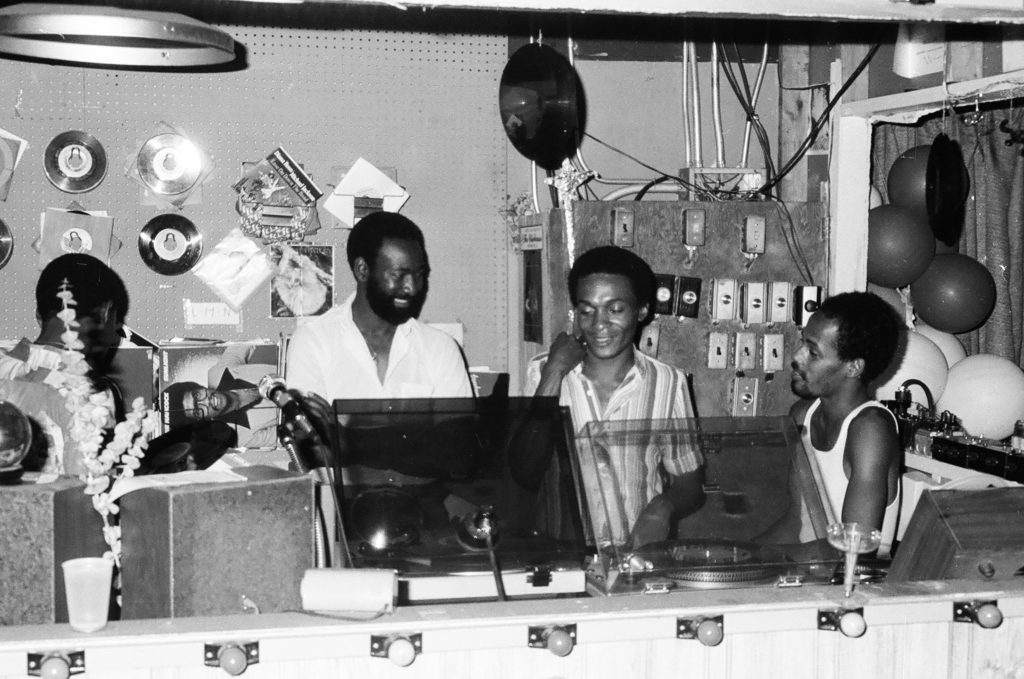

And what a place to dance! Starting from a system with “just two lights, a mere eight speakers, . . . within a year we had the best sound system in the world” according to Eddy. Richard Long, the audio designer for Studio 54 and Paradise Garage in New York City, designed the ClubHouse system. In subsequent years, Long used the ClubHouse to develop rigs before installing them in other clubs. Attracted by the equipment and the positive, energetic atmosphere of the crowd, DJs from other cities came to play. A constant stream of music—disco in the early days, house music later—fed the crowd’s energy. The music moved with the mood of the crowd. The club developed its own home-grown talent, training its own DJs as well as DJs from other clubs.[5]

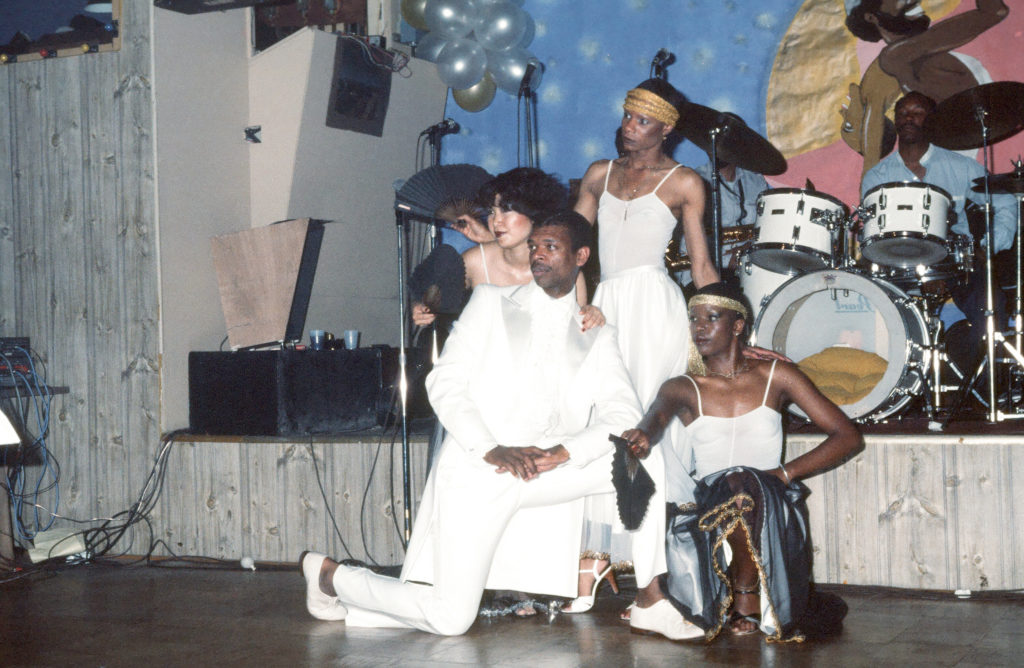

The ClubHouse’s reputation attracted stars, to perform or to party. Over the years Rudolf Nureyev, in town with the Royal Ballet, spent an evening dancing with the crowd. Phyllis Hyman, Nona Hendrix, the Weather Girls, Sylvester, and Patti LaBelle dropped by or performed. The ClubHouse developed its own dance corps, the ClubHouse Dancers, which opened for Sylvester at Constitution Hall, danced at Mayor Marion Barry’s 1982 inaugural, and performed at events in other cities.

Like the Loft, the ClubHouse was not a bar. Though it had a liquor license, liquor was only served at special events, often when outside groups rented the space.

Different nights drew different groups. The big night was Saturday, the night for the Black LGBTQ members and guests. ZEI night, for the straight community, came on Friday. Post Office night was Wednesday, according to Eddy, whose day job (which he did not quit) was at the Post Office. That attracted a primarily straight group. The city’s lesbian community partied Thursday nights. New Year’s Eve, Christmas, Thanksgiving, Halloween and St. Patrick’s Day had their own festivities. When Eddy said the ClubHouse was a place for everyone, he meant it. Though many White gay establishments discriminated against Black customers, the ClubHouse was open to all. Eddy estimated that 7-10 percent of the membership was non-African American.

On weekends, the ClubHouse opened late, generally around midnight. The crowd grew around 2 am as bars closed around the region. Patrons partied until the early hours. In later years, Cheeks organized fundraising dance marathons beginning Sunday at 5 am and running until the early afternoon.[6]

In addition to its regular schedule, the ClubHouse was known for two annual events. The Mother’s Day event commemorated its 1975 opening and honored members’ mothers with a special brunch or dinner.

Memorial Day weekend 1976 inaugurated Children’s Hour (“children” being a common name among LGBTQ people for themselves), the highlight of the year. Juicy Coleman and Russell Better led club members who started planning the invitation-only event months ahead. They chose a theme, such as cartoon characters, that dictated the appropriate attire. Invitations were prized and hard to come by as only 1,000 were sent. As its reputation grew, the Children’s Hour attracted people from across the country.[7]

The ClubHouse Gives Back

From the outset, the ClubHouse became something more than a social venue. Its space welcomed for many other activities, and not only for LGBTQ organizations. The space and its members proved ideal for political events. Reflecting the increasing political influence of LGBTQ organizations, Mayor Barry visited often and held a campaign rally there, as did Councilmember Arrington Dixon. During the 1980 presidential race, Walter Mondale’s campaign held a cocktail party fundraiser at the ClubHouse.

In October 1979 the ClubHouse held a rally and ball to raise benefitting the first National Third World Lesbian and Gay Conference at Howard University. That international conference brought together about 500 participants and coincided with the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.[8]

Then on Friday, July 3, 1981, the beginning of July 4th weekend, the New York Times published “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” by Lawrence Altman. This story is generally regarded as the first report in a national newspaper of what would become known as AIDS. In the early years of an epidemic that was ignored or stigmatized by society at large, members of the LGBTQ community organized themselves to care for those with the disease and advocate on their behalf. The ClubHouse provided space for early and continuing AIDS-related work for Black gay Washingtonians.

When the DC Coalition of Black Gays organized an AIDS Forum for Black and Third World Gays in conjunction with Whitman Walker Clinic in September 1983, the ClubHouse hosted the forum—the first significant outreach from the public health community to the Black LGBTQ community. From this point the club, its managers, staff, and members acted in critical roles in DC’s response to AIDS.

As a manager of the club, Rainey Cheeks saw first hand how the epidemic affected club members. No definitive numbers are available, but according to the Rainbow History Project, approximately 40 percent of club members were diagnosed as HIV-positive in the early years. Cheeks had already held meditation sessions and other health activities at the club. As the epidemic grew, he informally began to look out for club members diagnosed with AIDS, making sure that they had food, help with rent, transportation to medical appointments, and assistance with other needs.

Washington’s Black LGBTQ community realized that the city’s emerging AIDS efforts neglected their own community—people routinely dissed Whitman Walker clinic as “White Man Walker.” As a response, in 1985 Aundrea Scott and Cheeks launched Us Helping Us, one of the first organized responses to the epidemic focusing on the Black LGBTQ community by its own. Us Helping Us began by providing holistic care, counseling on diet, cooking, natural remedies, and mental health. From 1985 until it closed in 1990, the ClubHouse supported the organization as it grew to provide AIDS treatment and prevention services to the wider Washington area Black community.[9]

The Lights Go Out, the Sound Dies

By 1990 two social changes threatened the existence of the ClubHouse. First, new clubs such as Tracks, a large venue at 1111 First Street SE, competed for the younger Black LGBTQ audience eager for the latest new hot place. Tracks and other clubs in Southeast and Southwest DC had large outdoor spaces, something the ClubHouse did not.

Far more serious, the AIDS epidemic took its toll on the ClubHouse members. Though by the end of the 1980s new drugs, growing awareness, and activism in the LGBTQ community were beginning to temper the lethal impact of AIDS, it still raged—especially in the Black LGBTQ community. Hundreds of club members, including staff, were lost to the epidemic. With declining membership participation, door receipts declined, and the nonprofit club suffered significant financial pressure. Even though the broader ClubHouse community rallied to support their club, and Black gay social clubs, Best of Washington and the Associates among others, raised money to help keep the doors open, the club’s managers realized its run as a premier nightspot was coming to an end.[10]

Children’s Hour, Memorial Day weekend, 1990, brought the curtain down on 15 years of exhilarating, joyful celebration of Black LGBTQ life in Washington.

The ClubHouse Lives On

In the years from 1975 to 1990, DC’s Black LGBTQ women and men developed numerous movements and institutions to meet their needs. Sidney Brinkley launched his magazine Backlight beginning in 1979. The same year Howard University students formed Lambda Student Alliance. Enik Alley Coffeehouse at Eighth and I Streets NE emerged as a performance space for African American poets and musicians. The DC Coalition of Black Gays organized in 1978. Inner City AIDS Network (ICAN) provided a wide range of services to Black Washingtonians with AIDS. And there was the ClubHouse.

The ClubHouse’s remarkable 15-year run left an indelible mark on Washington. Guided by the vision and work of its founders, managers, and members, it provided a space for Black LGBTQ people to enjoy themselves and organize to meet the challenges confronting them.

Though the lights went out after Children’s Hour on Memorial Day weekend in 1990, the following Memorial Day, the first DC Black Gay Pride celebration opened at Banneker Field down the road from the ClubHouse. As Children’s Hour had, DC Black Gay Pride draws celebrants from across the country and around the world. Though today’s celebrants may not realize it, they keep the glow of Children’s Hour alive.

Us Helping Us grew. It survived the ClubHouse. It supports with service and advocacy the community that nurtured its birth.

—John P. Olinger, PhD, is a volunteer at the DC History Center.

[1] This post is based on Rainbow History Project’s exhibit on the ClubHouse curated by Steven Mandeville-Gamble from interviews conducted by Rainbow History Project’s volunteers. In 2021 RHP’s work on the ClubHouse continues with new interviews led by Delan Ellington; “ClubHouse Trailer,” SmallWonderMedia.

[2] Otis “Buddy” Sutson interview with Mark Meinke, Rainbow History Project Jan. 22, 2001, rainbowhistory.org

[3] “History: Origins & Location” SmallWondersMedia, “ClubHouse Trailer”; Eddy interview with Meinke.

[4] Ibid.

[5] ClubHouse Rainbow History exhibits, and John Eddy interview with Meinke, Apr. 25, 2005, rainbowhistory.org.

[6] Dr. Kwabena Rainey Cheeks interview with Meinke, Rainbow History Project, Aug. 3 [n.y.], rainbowhistory.org

[7] James “Juicy” Coleman interview with Meinke, Rainbow History Project Aug. 20, 2001, rainbowhistory.org.

[9] Cheeks interview with Meinke.

[10] Eddy interview with Meinke.