This biographical sketch, originally published as a “Person of Interest” feature in Washington History magazine, begins a series presenting brief profiles of noteworthy, often lesser-known figures in DC History to encourage further research and support future historical projects.

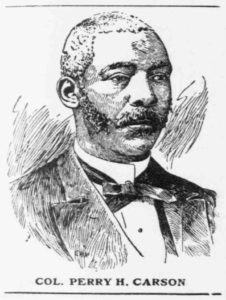

Perry H. Carson was a powerful African American leader in late 19th-century Southwest Washington, a political maestro whom the Washington Post dubbed “the Titanic leader of the colored race.” Carson rose from scrubbing streets to become a bailiff, saloon-keeper, and deputy U.S. marshal. Six feet, six inches tall, nearly 250 pounds, with dark skin and prematurely silver hair, the man whom the Washington Post described as the “tall black oak of the Potomac” cut an unforgettable figure as he sat in his bright yellow regalia astride an impressive gray horse at the front of each year’s Emancipation Day parade.[1]

Born free in Princess Anne County, Maryland, in 1842, Carson was arrested in Baltimore as a teen for helping abolitionists find safe houses for escaping slaves. He volunteered with the Union Army during the Civil War. After the war he found work in Washington as Mayor Sayles Bowen’s bodyguard and later as Governor Alexander Shepherd’s messenger. During this tumultuous period, he helped organize an informal regiment called the “Boys in Blue,” which defended black residents against attacks from Irish hooligans in Swampoodle on Capitol Hill. This quasi-military group served as a useful vehicle for political mobilization and gave him the title he carried throughout his career in politics: “colonel.”[2]

Though unschooled, Col. Carson was literate, and he had a magnetic presence and a powerful speaking style. In the 1870s he became the most prominent leader of working-class black Washington; the Evening Star claimed that Carson “practically controlled the great colored vote of the District for years.” After Congress stripped all D.C. residents of the ballot in 1874, Carson exerted his influence by organizing and leading the annual Emancipation Day celebration. An active Republican, he served as Washington’s black delegate to the quadrennial Republican National Conventions from 1880 to 1900, a position that helped him control local party patronage. He also formed the “Blaine Invincibles” to support statesman and perennial Republican presidential candidate James G. Blaine of Maine.[3]

Carson challenged white city officials repeatedly about police mistreatment of black residents, an issue of tremendous importance to the black working class in late-19th-century Washington. The once-integrated city police force became almost exclusively white after Reconstruction, and there were numerous incidents in which white officers killed black men under suspicious circumstances. “Negroes are not respected” by police, Carson told one crowd in 1891, and he urged black citizens to take their case directly to Congress. In 1895 he called D.C. police “assassins” and led an “indignation movement” to get city officials to prosecute an officer for the slaying of a young black man in Hillsdale.[4]

Carson adroitly tapped the deep class conflicts within the black community, at times questioning the commitment of the black upper class to its less-advantaged brethren. Writing to a congressional committee, he denounced black attorney and politician John M. Langston as a “white man’s man” who was not “in his taste, habits, or association, a negro at all.” He clashed often with Calvin Chase, the acerbic editor of the Washington Bee, the city’s most prominent black newspaper. Chase wrote that Carson and his rough-hewn supporters were “ignorant” and a “disgrace.” Their feud—and more broadly the clash between the black working class and well-to-do black elites—erupted publicly over the style and control of Emancipation Day celebrations in the mid-1880s. Despite Chase’s attacks, Carson remained popular with the masses. “He may not suit the dandies of the colony,” wrote one admirer, “but he suits the bone and sinew.”[5]

Carson’s influence waned after the turn of the century. He remained employed as a city watchman until 1908, when the city commissioners passed him over for a promotion. He resigned in protest, but his career was over. He died of pneumonia a year later at the age of 67.[6]

—Chris Myers Asch was Editor of Washington History magazine from 2015 until 2019. This profile first appeared in Washington History 28-1 (spring 2016).

Endnotes

[1] Wm. H. Boyd, Boyd’s Directory of Washington and Georgetown (Washington, 1880), 197; “Guiteau Still Alive,” Washington Post, Nov. 20, 1881; “A March Through Rain,” Washington Post, Apr. 17, 1883; “Perry Carson is Dead,” Washington Post, Nov. 1, 1909; Colored American, Jan. 27, 1900.

[2] Perry Carson is Dead,” Washington Post, Nov. 1, 1909; “Col. Perry Carson Passes Away,” Afro-American, Nov. 6, 1909; “Letter from Washington,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 19 1873; “Carson Claimed by Death,” Washington Bee, Nov. 6, 1909.

[3] “The Fire Board Fight,” Washington Post, Sep. 17, 1879; “Colored Leader Dead,” Evening Star, Nov. 1, 1909.

[4] “Talk in a Fiery Vein,” Washington Post, Dec. 22, 1891; Washington Times (morning), Jul. 23, 1895; “Seeking Green’s Arrest,” Washington Post, Mar. 9, 1895.

[5] Perry H. Carson to R.L. Singleton, Oct. 30, 1888, Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives, 51st Cong., 1st sess., 1889-90 (Washington: GPO, 1890), 34-35; “The Mob Reigns,” The Bee, Apr. 12, 1884; Mitch Kachun, Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 207-232; “Stand By for Carson!” Washington Post, Dec. 14, 1895.

[6] “Colored Leader Dead,” Evening Star, Nov. 1, 1909; Perry Carson is Dead,” Washington Post, Nov. 1,1909; “Col. Perry Carson Passes Away,” Afro-American, Nov. 6, 1909.