In recognition of Women’s History Month, DC History Center volunteer archivist Dave Wood describes a favorite collection: the 66 scrapbooks of Washington socialite Adelaide Heath Doig. Adelaide’s ephemera take us back to the era of teas, gracious living, and privilege as enjoyed by upper-crust White Washingtonians. This “Person of Interest” is just a beginning to what we hope one day will be a fuller story.

A Well-Connected Life

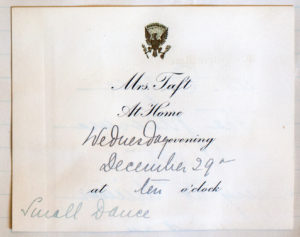

Adelaide Heath Doig (1891-1962) was perhaps the most well-connected Washingtonian that you’ve never heard of. Invitee to numerous White House functions, spanning several presidential administrations? Check. Guest at balls, dances, teas, luncheons, and dinners at the private homes of Washington luminaries such as Evalyn Walsh McLean, Larz Anderson, the Levi Leiters, the Charles Carroll Glovers, the Walter Tuckermans, and the Montgomery Blairs? Check. Soirees aboard U.S. Navy vessels at Newport, Rhode Island? A weekend at John D. Rockefeller’s estate near Bar Harbor, Maine? Adelaide was there.[i]

Historians hadn’t heard of her either. I became aware of her because the DC History Center holds a collection of her scrapbooks—66 in all—and I took on the assignment of preparing our detailed guide to their contents. The scrapbooks, now MS 0846 Adelaide Heath Doig scrapbook collection, were donated to the DC History Center by Adelaide’s cousin, Elizabeth Loomis, in 1962. While they begin to tell her story, future researchers will be able to add much more.

So who was Adelaide? In short, she was a prototypical member of what the press then called Washington’s “resident Society.” The status of these people stemmed not necessarily from wealth, but rather membership in prominent and affluent White families that had resided in the District, Maryland, or Virginia for generations. Adelaide was born on November 5, 1891, the only child of the former Anna Fauntleroy Barnes and Hartwell Peebles Heath. Her mother died when the girl was just seven years old. Soon after, her father moved to New York, leaving Adelaide to be raised in genteel comfort by her maternal grandmother Mary Fauntleroy Barnes. They lived fashionably close to the White House at 1722 H Street NW, where the World Bank is today.

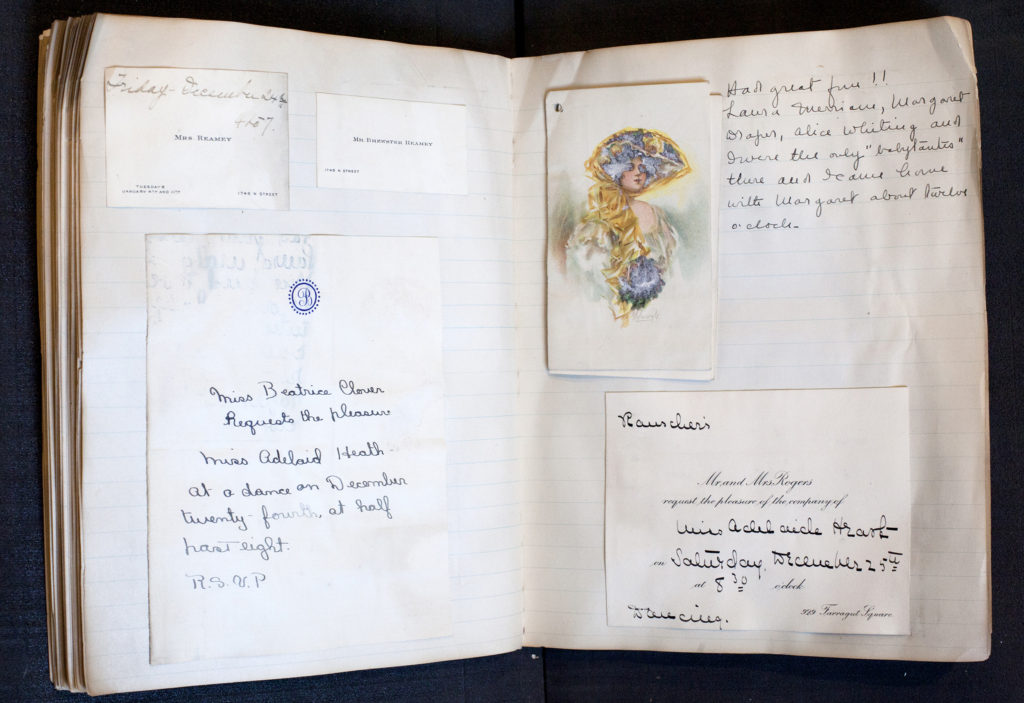

While Adelaide was not personally wealthy, her friends were exclusively from upper-crust families headed by government officials, military officers, or well-to-do professionals and businessmen. Starting at age 14, and continuing to the end of her life, Adelaide, like many of her friends, compiled scrapbooks that today richly illuminate the world she inhabited. The keeping of scrapbooks with party invitations, press clippings, photographs, correspondence, and the like, was a privilege taken by many individuals with both access to society and the leisure time to document it all.

The more illustrious members of Washington’s resident society (later and less charitably dubbed the “cave dwellers”) were often found on the edges of political power, and occasionally at its helm. Adelaide’s family was no exception.

Her maternal grandfather Joseph Barnes was appointed surgeon general of the United States Army by President Lincoln, and consequently was at Lincoln’s bedside in the Petersen house at his death. (Still surgeon general 16 years later, Barnes was one of the physicians who attended the wounded President James A. Garfield without the aid of modern antiseptic technique. Garfield subsequently died of infection).

Adelaide’s mother Anna had been a bridesmaid at the White House wedding of President Grant’s daughter Nellie. Her father’s family belonged to Virginia’s plantation aristocracy, having owned land south of the James River since Colonial times.

Adelaide’s grandfather, Roscoe B. Heath, an attorney in Richmond, Virginia, is listed as the owner of one enslaved person in the 1860 census. Other Heath family landowners likely also benefited from the labor of enslaved people, but more research is needed to confirm this. Adelaide’s scrapbooks contain no reference to the subject. Adelaide’s grandmother Heath was the former Betty Mason, whose father John Young Mason, of Greensville County, Virginia, was elected to three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He also served as a federal judge, attorney general, and finally U.S. minister to France under Presidents Pierce and Buchanan.

Further cementing her ties to the city’s upper echelons, Adelaide’s godfather was Charles Carroll Glover, the Riggs National Bank president behind the creation of Washington National Cathedral and Glover-Archbold Park. Her godmother was the wealthy Emily McLean, whose husband John owned the Washington Post (their son Edward married mining heiress Evalyn Walsh, flamboyant owner of the supposedly cursed Hope diamond). Adelaide worshiped at St. Johns Church, Lafayette Square (known as the church of the presidents) and attended (though did not graduate from) Miss Madeira’s School (now the Madeira School in McLean, Virginia) when it was a fashionable new institution located near Dupont Circle.

A complete list of Adelaide’s friends would fill many pages. But this sample shows her proximity to power and fame in official Washington. She counted as friends sisters Laura and Louise Delano, daughters of Frederic Delano and first cousins of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Martha Bowers was the daughter of the solicitor general under President William Howard Taft, and later the wife of the president’s son Robert Taft. Adelaide also enjoyed the company of Louise Cromwell, later wife of General Douglas MacArthur, and Esther Slater, later wife of Secretary of State Sumner Welles. We know about these friends, because Adelaide preserved so much of their correspondence over the years. One example: Adelaide’s friend Virginia LeSeure, granddaughter of Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon, lost her mother in 1935. Adelaide’s sympathy note evoked this response from Virginia: “I appreciated so much your note of understanding sympathy—you well know how we have lost a mother. . . . What changes since our comparatively carefree days in Washington and how long ago it all seems.”

More than a Debutante

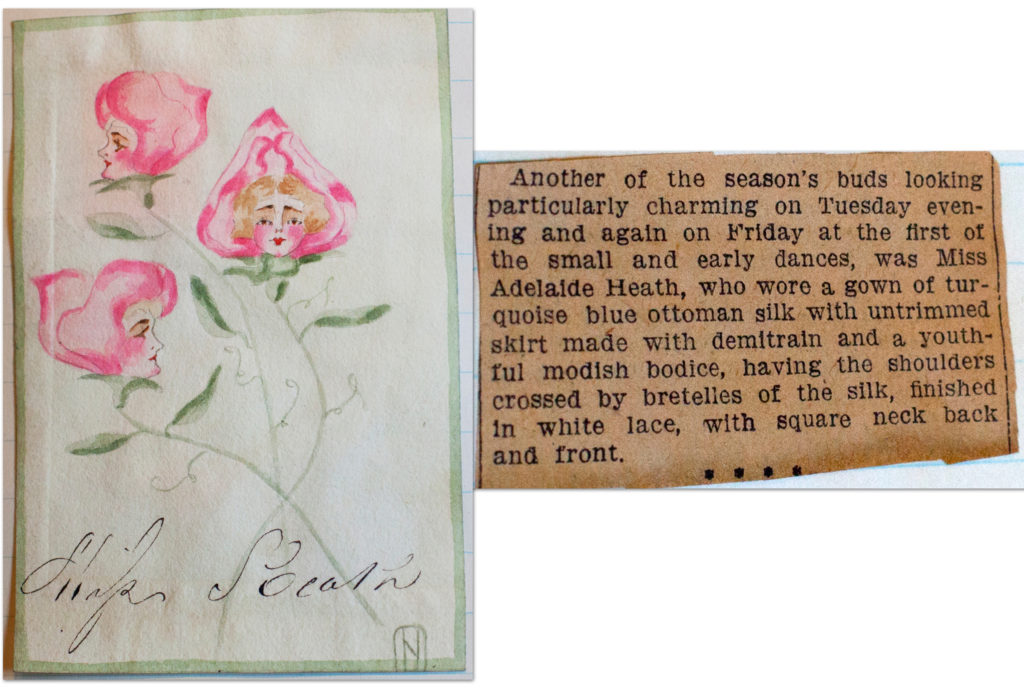

In 1909 Adelaide, age 18, made her debut—a carefully choreographed season of luncheons, dances, and social events to introduce her to society, often culminating in a formal ball. Adelaide’s initial debut event was a modest afternoon tea given by family friend Clementine Smith. She seems to have generally followed the strictures of behavior for unmarried young ladies of her social standing during the ensuing decade. After her grandmother’s death in 1912, she lived with her aunt Mary Mason Heath. Although Adelaide inherited her grandmother’s house, she rented it out, possibly both for financial reasons and for the sake of propriety. The scrapbooks for this time contain a wealth of engraved invitations, calling cards, personal notes, and other correspondence. Tickets and programs record her theater-going, church bulletins attest to her devotion to the Episcopal Church, and newspaper clippings capture her name and those of her circle in the social news.

But Adelaide was more than a debutante. She also put in many hours acting on her concern for the welfare of others. Like many of her friends who did not need to work for a living, she helped run benefits for the Red Cross, Boy Scouts, YWCA, and others. Perhaps less typically for the time, she was also keenly interested in sports—during childhood summers spent in Winchester, Virginia, she played on a girls softball team—and her scrapbooks contain many sports tickets, programs, and newspaper articles. The term “idle rich” did not apply (she was neither). In 1916, perhaps to augment the income from the rental of her house on H Street, Adelaide was employed as a governess by the wealthy Leiter family of Dupont Circle. In 1918, during World War I, she joined the thousands of young women who flocked to the District to support the war effort as “government girls.” Adelaide was assigned to the code room at the U.S. Department of State. Though the scrapbooks reveal little about her activities there, code room workers typically assisted in decoding secret, encrypted messages from diplomats and others abroad.

Many of Adelaide’s friends married after their debut season in the winter of 1909-1910. Beside the announcement of yet another engagement—that of Ellen Biddle Shipman in August, 1917—Adelaide dryly noted, “And still they come!” She did not lack for suitors; the names of at least 15 young gentlemen, including military officers (Captain Lacey Hall, Commander Theodore Jewell, Captain Ridley McLean) appear in her scrapbooks as escorts to various social functions.

But it was Army Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Haldane Doig of San Diego, California—whose name first appears as a member of a “movie party and supper at Café St. Marks” on March 19, 1919—who eventually won her hand. On June 8, their engagement was announced in the Washington Post, the Washington Star, and the Washington Times, the latter noting, “This announcement is of widespread interest. Miss Heath being not only prominent in the social life of the capital, but an active worker for many philanthropic organizations.” They were married at the Church of the Epiphany on G Street NW in October 1919.

Interludes in the West

Doig’s Army assignments took the couple far from the District, first to Washington state, then the Chicago area, and finally St. Louis, Missouri. But Adelaide maintained ties to her DC past through a voluminous correspondence with friends. During annual visits to the city, usually coinciding with her birthday, her friends celebrated her with luncheons, teas, and dinners. Happily for historians, she continued documenting her life via scrapbooks. They show her keen interest in politics and public affairs—and Adelaide’s use of the technology of her day to keep in touch. For example, she noted that she listened to the entire 1929 Herbert Hoover inaugural on the radio. And beside a clipping about Franklin Roosevelt securing the Democratic nomination for president, she wrote: “Thursday, June 30, 1932. Sat up until 3:15 in the morning [listening to the radio] when they started to poll the New York delegation.”

The scrapbooks show that in the years away from DC Adelaide maintained a busy, if less-illustrious, social life while continuing charitable work. She saved records not only of theater parties, teas, luncheons, and dinner outings, but also of volunteer activities such as delivering foodstuffs to needy families at Christmas. After Arthur left the Army in 1928, the couple, who had no children, remained in St. Louis where he established and managed the local Gray Line sightseeing bus enterprise. They lived modestly but well, taking major annual vacations. One wonders if Adelaide might have missed the social life of her early years in Washington, but the scrapbooks reveal no such hint. They depict what appears to have been a happy marriage, regularly noting wedding anniversaries, and including telegrams from Arthur (many signed simply “Beau”) to Adelaide whenever she was away. Following months of ill health, Arthur died in January 1943. Adelaide continued her annual visits back to Washington, but—for reasons not explained in the scrapbooks—remained in St. Louis for a few more years.

Home Again to DC

In 1949 Adelaide returned to DC permanently, taking an apartment at 1921 Kalorama Road NW. A society column account of her return quotes Adelaide: “It is the first time in 30 years that I am really at home to stay, and it promises to be great fun.” She resumed her charitable work, serving on the Board of the Washington Home for Incurables. She also indulged her unflagging interest in current events and politics. A member of the League of Women Voters, she was a lifelong friend of Senator Robert Taft and his wife Martha, and worked on Taft’s unsuccessful presidential primary campaigns in 1948 and 1952. (Following Robert Taft’s death, she pasted in a 1955 news article about congressional approval of the Taft Memorial tower on Capitol Hill. Beside it she wrote, “How Bob would have hated such a useless memorial!”) Though an active Republican, Adelaide was apparently not rigidly partisan, and her early years in Washington seem to have provided the basis for a broad and well-informed perspective. (She noted beside a 1961 newspaper transcript pasted into her scrapbook, “[Democrat John] Kennedy’s Inaugural address was splendid, I thought.”)

Adelaide’s health declined in the late 1950s. She died on March 8, 1962. As the wife of an Army officer, she was buried beside her husband in Arlington National Cemetery.

More to Learn

While Adelaide Doig’s scrapbooks profusely chronicle her activities, they are not intimate diaries. Perhaps emblematic of her time and place, she rarely expressed opinions on weighty subjects, though she could be pithy about the mundane. Beside an article with photos about Washington’s new street lights, a disapproving Adelaide wrote: “August 1958. These awful new lights installed on 20th and Kalorama Road, right outside my apartment windows. Unattractive looking by day and the light is a queer green at night.” Understandably she may have omitted less-pleasant aspects of her life. A couple of references to lip-reading classes suggest that her husband may have become deaf, but she made no comment about how difficult that was for her.

Adelaide’s scrapbooks are a fascinating time capsule capturing the public activities within one social strata in early- and mid-20th-century Washington. The documents she preserved, and her many annotations, bring the past alive. But they are just a starting point, fertile ground for both professional researchers and the casual reader interested in social history and in real-life characters from Washington’s past.

—Since retiring from the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 2008, David G. Wood has volunteered as an archivist in the DC History Center’s Kiplinger Research Library.

[i] Unless otherwise noted, the information on Adelaide Heath Doig’s life comes from MS 0841, Adelaide Heath Doig scrapbook collection, 1846-1962, DC History Center.

[ii] Eighth Census of the United States 1860; “Mason, John Young,” History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, history.house.gov/People/Listing/M/MASON,-John-Young-(M000220)/.