These resources on Salvadoran immigrant communities and the Latina/o/x presence in Washington offer a beginning to the ongoing historical documentation of these relative newcomers to Washington, DC.

SALVADORAN AMERICANS AMID THE LATINA/O/X WORLD OF DC

Today DC’s Latina/o/x residents account for approximately 12% of the city’s population. While Salvadoran Americans are the fourth largest Latina/o/x group in the United States, they are by far the largest Latina/o/x group in DC.

Although DC has had a Mayor’s Office of Latino Affairs since 1976, the Latina/o/x communities in general still lack political representation at a city level. This is also a particularly fraught time in our national history, when federal policies to support immigrants, such as the reprieve from deportation provided by Temporary Protected Status, were threatened by the Trump administration.

To understand the impact of the absence of political representation, it’s helpful to go back in time. The 1970 Census—the first to try to identify individuals of Hispanic origin or descent—counted 17,561 Latina/o/x people. But those numbers were a far cry from the actual number. Because city services are delivered in large part based on census numbers, undercounting would have disastrous effects on residents who were already underserved. The Census undercount was a galvanizing force for advocates of representation and civil rights.

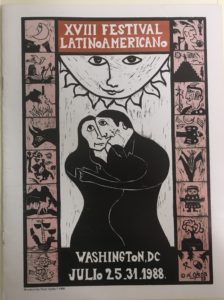

The Latino Festival was established in 1970 to bring together disparate communities with a common goal: literally to show the city and its government that they existed. That celebration continues more than 50 years later as Fiesta DC. The Latino Festival addressed the issue of defining community and interests. To many Washingtonians, Black and White, these 20th-century immigrants appeared to be a monolithic, Spanish-speaking population competing for turf in Adams Morgan, Mount Pleasant, and Columbia Heights. But for the people—who moved here from Puerto Rico, Cuba, Honduras, Colombia, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Panama—they were anything but monolithic. Their nationalities and their class and race differences, not to mention their varying reasons for leaving behind their homeland, were stronger markers of identity than commonalities of language.

These decades-old issues continue to reverberate through successive waves of gentrification, assimilation, and political change. The immigrants’ history is found throughout the DC Metropolitan Area. To provide some context to this picture, we offer these resources on the Salvadoran immigrant community.

“Forever Wachintonian Salvadorean”: Community, Culture, and Representation (Video)

On March 18, 2021, Professor Ana Patricia Rodríguez and oral historian José Centeno-Meléndez discussed how DC’s Salvadoran immigrant community maintains its cultural identity in DC. They were joined by special guest Abel Nuñez, executive director of CARECEN, for a conversation about issues of Salvadoran political representation and the impact of both local and federal politics on the community.

View the video here.

Recommended Reading

“Becoming ‘Wachintonians’”: Salvadorans in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area,” by Ana Patricia Rodríguez, Washington History, 28-2 (2016).

Rodríguez, a professor of literature, examines cultural production of Salvadoran immigrant poets, painters, and novelists. She notes that robust cultural representation is not mirrored in local political representation.

“‘Tirarlo a la Calle/Taking It to the Streets’: The Latino Festival and the Making of Community,” by Olivia Cadaval and Rick Reinhard, Washington History, 4-2 (1992).

Written the year following the Mount Pleasant uprising, the article traces the roots of the Latino Festival, which began in Adams Morgan in 1970 in part as a response to undercounting of DC’s Latino residents in the U.S. Census.

“1991: Mount Pleasant,” by Patrick Scallen, Washington History, 32-1/2 (2020).

Scallen recounts the 1991 uprising following the wounding of Salvadoran immigrant Daniel Gomez by a police officer. It appears in Meeting the Moment, a special issue of Washington History magazine published as a response to the global pandemic and ongoing Black Lives Matter protests. In this issue, Washington History challenged DC historians to look back into their research and ask: what could DC’s past tell us about how we arrived at this moment?

“Carlos Manuel Rosario,” by Amber N. Wiley, Washington History, 30-1 (2018).

In a city where class and cultural differences separated various Latino immigrant communities, Puerto Rican immigrant Carlos Rosario focused on the commonalities – language, along with social and political needs – to establish a sense of Latinidad – pan-Latin identity.

“’Yes, It Can Be Done’: A Photographer’s Record of Latino Washington, D.C.,” by Rick Reinhard, Washington History, 29-1, 2017.

A photographer and community activist, Reinhard has documented Latino DC since the 1970s. His vivid photographs capture the founders of the LatiNegro Theater Collective and CARECEN, and the many protest marches, celebrations, and artistic expressions of the communities.

The 2019 issue of Washington History offers a special package on the significant role Mount Pleasant plays in the Latina/o/x community based on an oral history/photo exhibit centered on La Esquina, where Mt. Pleasant Street meets Kenyon Street NW. Olivia Cadaval presents the project in “About La Esquina / The Corner,” followed by Rick Reinhard’s photo essay, “La Esquina Gallery.” In “A Third Citizenship,” poet and performer Quique Avilés offers his personal narrative of living in the neighborhood.

“Images of an El Salvador Town Transformed by Migration,” by

From Our Collections

The Kiplinger Research Library has reopened with remote reference services only (March 2021). Once the library is open for on-site visits, researchers will have in-person access to these key collections. Click the links for more details from our catalog.

“Hispanic organizations of the Washington Metropolitan Area : an analytic profile : a study of private, secular, local Hispanic organizations based in the Washington, DC Metropolitan Area,” by Tia Ann Murchie-Beyma, Occasional Paper Series, Center for Washington Area Studies 8, George Washington University (1990) P 0333

“Hispanic organizations of the Washington area : an annotated directory : a directory of private, secular, local Hispanic organizations based in the Washington, DC Metropolitan Area” by Tia Ann Murchie-Beyma. Occasional Paper Series, Center for Washington Area Studies 9, George Washington University (1991) P 2645

“The Latino DC History Project: 2009-2010 synopsis” by Elaine A. Pena (Smithsonian Institution 2010) P 5030

“The Latino community : A reference bibliography,” by Sandra Barrone (1991) P 7116

Creating A Latino Identity in the Nation’s Capital: The Latino Festival, by Olivia Cadaval (Garland, 1998). (GT4811.W37 C33 1998)

A go-to text that begins to document the creation of a Latino community in Adams Morgan, using the annual Latino festival as its focal point. A good portion of this now-out-of-print book is dedicated to Salvadoran women’s roles as food-makers in the community.

Waiting on Washington: Central American Workers in the Nation’s Capital by Terry A. Repak (Temple University Press, 1995). (HD8085 .W183 R46 1995)

This book traces the migration of Salvadoran women to D.C. who were recruited to work as domestics by embassy personnel and other international organization workers. Though Repak focuses on El Salvador as a case study, she also very briefly mentions other Central and South American women whose migration trajectories were similar.

To Learn More

Many thanks to Ana Patricia Rodríguez, PhD, and José A. Centeno-Meléndez

for their guidance in developing this reading list further exploring the

contributions of, and challenges faced by, DC area Latina/o/x communities.

Latinas Crossing Borders and Building Communities in Greater Washington, ed. Raúl Sánchez Molina and Lucy M. Cohen (Lexington Books, 2016).

An anthropological approach to examine ways in which Latina and Latino immigrants have adapted to and coped with life in the DC metro area.

Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place, by Gabriella Gahlia Modan (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007).

Modan’s ethnography of Mount Pleasant documents how this neighborhood underwent rapid gentrification. Modan also demonstrates how DC has been (and continues to be) portrayed as a “Black and White” city despite its multi-ethnic and multi-national makeup.

“No Hay Negroes”: Black Erasure in El Salvador, by Danielle Parada.

Parada uses infographics on her Central American Research Collective platform to bring attention to anti-Blackness within the Salvadoran community.

‘”Black Behind the Ears’—and Up Front Too? Dominicans in ‘The Black Mosaic,'” by Ginetta E.B. Candelario, Public Historian, 23-4 (2001).

Candelario specifically addresses the Dominican community in this analysis of an Anacostia Community Museum exhibit, as an example of the continued privileging of a U.S.-centric concept of African-American history and identity. See also her subsequent book, “Black Behind the Ears”: Dominican Racial Identity from Museums to Beauty Shops (Duke University Press, 2007). Candelario’s work is key to understanding longer legacies of Latin American and Caribbean migrations to the area. One chapter highlights the role Black Dominican women played in creating a notion of a shared Latin American/Latino identity from as far back as the 1940s.

“Our Voices in the Nation’s Capital Creating the Latino Community Heritage Center of Washington, D.C.,” by Olivia Cadaval and Brian Finnegan, Public Historian, 23-4 (2001).

The authors address the role of community-driven and community-focused cultural heritage organizations in encouraging participatory democracy in neighborhoods that traditionally lacked political clout. Cadaval and Finnegan detail how the Latin American Youth Center, Smithsonian, DC Humanities Council, and Historical Society of Washington, D.C. collaborated on the Heritage Center in the 1990s.

Voces Sin Fronteras: Our Stories, Our Truth, by Latino Youth Leadership Council of the Latin American Youth Center (Shoutmouse Press, 2018).

These “true comics” present the immigration experiences of 16 local young people in graphic form.

“Why Nearly Every Salvadoran Restaurant in DC Serves Mexican Food,” by Lautaro Grinspan, Washingtonian, December 18, 2018.

Exploring the role of food as cultural expression and restaurants as a gateway for immigrants to establish themselves in DC.

Knocking on the Door of The White House: Latino and Latina Poets in Washington, D.C. , ed. Luis Alberto Ambroggio, José R. Ballesteros, Carlos Parada Ayala (Zozobra Publishing, 2010).

This is the first Spanish/English anthology of Latino/a/x poetry from the DC Metropolitan Area.

La Horchata Zine, 2017-2019, by Kimberly Benavides and Veronica Melendez.

Released in limited print editions, this ‘zine was founded in Mount Pleasant to reflect artwork created by the Central American diaspora.

“¿Dónde estás vos/z?: Performing Salvadoreñidades in Washington, DC,” by Ana Patricia Rodríguez in Imagined Transnationalism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Rodríguez examines text-based performances by Quique Avilés, Culture Clash, and Lilo González and los de la Mount Pleasant, to explore Salvadoran cultural identity construction in DC, Maryland, and northern Virginia. These themes are also examined in Chapter 6 of Rodríguez’s Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literatures, and Cultures (University of Texas Press, 2009). Chapter 6 traces Central American migratory experiences after the 1990s and explores the cultural production of DC “wachintonians” Mario Bencastro, Karla Rodas, and others.

Build Your Library

Check out these local bookstores: Mahogany Books, Loyalty Bookstores, Sankofa, Wisdom Book Center, Harambee Books, Second Story Books, Politics and Prose

Help Us Identify Latina/o/x Resources!

The DC History Center recently launched an initiative to compile a Latina/o/x resource guide to bring attention to the holdings of local repositories and identify records held in private hands. The goal is to help researchers gain a fuller understanding of the state of records created by, for, and about all of the city’s diverse Latina/o/x communities.

The archival resource guide is a project conducted by the DC History Center in partnership with the University of the District of Columbia’s Political Science Department. The initial phase, closing April 23, 2021, will collect information with the collaboration of local repositories and through contributions by the public. All are encouraged to participate.