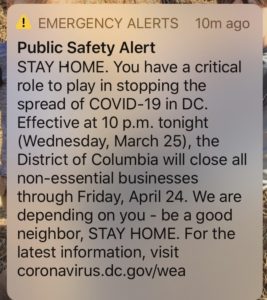

Exactly a year ago, the DC History Center launched In Real Time, a short-term—or so we thought—collecting initiative to capture the daily impact of the pandemic as Washingtonians experienced it. It was also my first project as a newly minted executive director.

Little did we know that 2020 would morph into an extended period of political disruption, from street protests reacting to the unconscionable murder of George Floyd to the insurrection at the Capital. My first year on the job did not quite turn out the way that I expected.

As we unveiled In Real Time, we also realized that the DC History Center, in its 127 years of operation, had never before committed to collecting stories, archives, or photographs of an event as it occurred.

Historians have typically worked at a remove, putting time between themselves and their subjects. A healthy distance of at least 50 years was required before historians could weigh in. This was the difference between history and journalism, they would say.

In fact, I previously worked for the DC History Center during 9/11. It didn’t even occur to us then that evidence of the impact of that tectonic event was worthy of being collected. So, what changed?

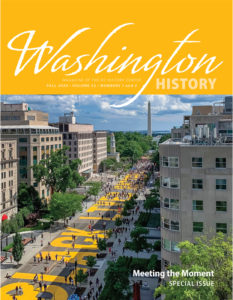

Clearly something profound has shifted since 2001. In response to COVID-19, our peers nationwide unveiled similar collecting initiatives, prompting extensive coverage in the Washington Post and New York Times. Here in DC, the DC Public Library, the Anacostia Community Museum, and Humanities DC also stepped up their collecting efforts. As Black Lives Matter protests filled Downtown, the National Museum of African American History and Culture took the lead in saving the evidence.

It seems that the pull to collect, preserve, and archive was felt acutely and deeply in 2020. Our self-awareness of living in a historic moment, even when we thought the pandemic would be over in a matter of weeks, led us to myriad acts of self-expression—a diary, a photograph, a dance move on Tiktok—and much more, if you’re Taylor Swift.

Where we once thought that Great White Men of Years Past shaped the course of history, our field experienced a profound rethinking in the 1960s. Now, we have come to believe that the stories of everyday Washingtonians are just as important, and perhaps even more revealing, than what happens in the halls of power. Thanks to the collective impact of the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, we are even more inclined to trust these everyday voices and their honest truths.

In short, we are all speaking, listening, responding to one another constantly. The quality of our attention sometimes flags, but the sheer abundance is unmistakable. The historians of the future have their work cut out for them. They won’t have much access to the hand-written letters and carefully printed photographs we prize today. An over-abundance of data— tweets, emails, and smartphone pictures—will offer 360 degrees of authentic, unprocessed evidence. Making sense of all that won’t be easy.

For right now, I find myself moved by the magnificent manifestation of so many diverse and beautiful Washington voices—each of them unique, special, and meaningful—contributing to the historical record. Each one, important. Many of them, deeply moving in their humanity and vulnerability.

At the DC History Center, we are humbled to have collected at least a small sliver of these stories, fulfilling a profound need to preserve and remember, especially those we’ve lost.

As we emerge from this crisis, striving for a better, more just, and equitable tomorrow, this work stands as a powerful testament to what Washingtonians are capable of—even under the direst of circumstances. Now, we can ask, how will these collections help us recover, transform, and reinvent ourselves and our beloved city? How can they become touchstones in the journey to our better selves? In short, what will this history teach us?