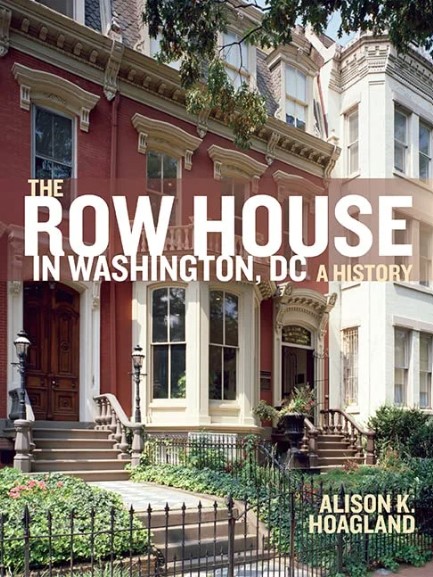

Alison K. Hoagland is the author of The Row House in Washington, DC: A History.

Washington, DC is a row house city. Row houses number more than any other type of housing, they line the streets of our neighborhoods, and they help create the low scale that we appreciate so much. Writing about them seemed natural—shouldn’t we know more about this characteristic building type? And no one had written a book on them before.

So I plunged in. I moved to this city in 1977 into a second-floor flat of a row house designed to be single-family. I studied row houses in conjunction with the DC Preservation League’s Downtown Survey in the early 1980s (yes, there are/were row houses downtown!). I maintained a lingering interest in row houses as I pursued a career in architectural history and historic preservation across the country. Finally, a few years ago, I was ready to pursue this topic as a book. Because, everyone loves row houses, right?

Well, no. As I developed this book, I slowly realized that they were not always popular. And that affected where they could be built and who lived in them.

Washington, DC was planned to be a row-house city. George Washington’s 1791 building regulations, which he issued concurrently with the first sale of lots, included references to party walls, and early developers built some rather grand rows in the 1790s. Georgetown and Alexandria were full of them. But the city of Washington was slow to develop and it wasn’t until after the Civil War that housing construction really took off. Most of these new buildings were row houses. Neighborhoods such as Capitol Hill, Dupont Circle, Foggy Bottom, and Shaw all filled in during that period.

These neighborhoods were developed by speculative builders who tended to build groups of three or four—sometimes more, sometimes less, but rarely the whole side of a city square. While the design of each house in a row might have been repetitive, the different rows lent variety to the street. With late-19th-century styles featuring bay windows, turrets and towers, busy rooflines, and a mix of materials, row houses displayed lively facades.

This diversity changed in the early 20th century. “Operative builders,” who created large companies that consolidated marketing, financing, design, construction, and sales under one roof, dominated the building industry. These operative builders constructed long rows of houses, occupying the whole side of a square, or sometimes all four sides of a square. The row houses tended to be two stories, with front porches and a compact, repetitive design. They were immediately perceived as monotonous, uninspired, and cheap.

The term row house arose at this time, and it was not meant to be flattering. Row house rarely appeared in the 19th century Instead, a house would be referred to as being part of a block. Developers also called them inside houses, as opposed to those on the ends of rows, which had windows on one side. When the term row house appeared in the early 20th century, it was pejorative.

Washington’s first zoning code, issued in 1920, excluded row houses from much of the city. Not only the area west of Rock Creek Park (except Georgetown, Glover Park, Burleith, Foxhall Village, and Woodley Park), but also the whole northern tier of the city, as well as most of the area east of the river (except Anacostia village). The Washington Post explained, “row houses cannot be put up in any part of town which they have not already invaded” (July 27, 1920, p. 12).

Theodor Horydczak, photographer, ca. 1920-50, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Theodor Horydczak Collection.

Developers, though, saw a market for the row house and deplored the fact that so many would-be homebuyers would be forced into apartments or out of the city altogether because there was not enough land zoned for row houses. One strategy that they employed was to relabel the row house as a group home and, later, after World War II, as a townhouse. Washington Post critic Wolf von Eckhardt explained, “you might say the town house is a row house with class” (July 24, 1966, p. G7).

Despite its shaky reputation, the row house has survived to become highly desirable. Prices for this once-modest building type exceed $1 million in many parts of the city. The row house is a good candidate for “smart growth,” being dense (occupying little land area) and energy-efficient (with abutting walls saving energy), but offering the privacy of a single-family home. The row house is also Washington’s characteristic building: maybe not always wanted, but certainly appreciated by those who have lived in them. Row houses define our streets, make us neighbors, and give our city its distinctive appearance.

You can read more from Alison in The Row House of Washington, DC: A History, available at the DC History Center store.