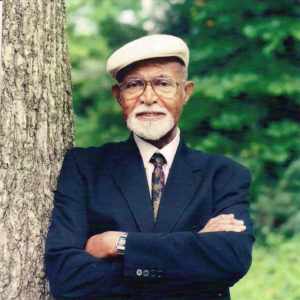

The DC History Center joins Washingtonians in paying tribute to architect and activist Charles Cassell.[1]

Mr. Cassell is remembered for his work as an architect, his commitment to civil rights and social justice, his dedication to historic preservation, and his devotion to jazz. He was an outspoken, dramatic, and persuasive voice for important causes over a lifetime of paying attention to what he believed mattered to his many communities here in Washington.

Charles Cassell was born in Washington on August 5, 1924, to the former Martha Mason, a teacher, and Albert I. Cassell. The senior Cassell was a widely esteemed architect, the second Black graduate of Cornell’s School of Architecture, and a major force in the look of today’s Howard University campus. Constrained by pervasive racial segregation, Albert Cassell aspired to build whole communities for African Americans where they could live free of racist limitations. He designed and built Mayfair Mansions in Northeast DC and designed a site plan extending to today’s Kenilworth Courts. An unprecedented planned recreational community for African Americans on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, the only Albert Cassell Project that was not realized, is the focus of a Washington History magazine study by Peter Sefton and Sally Lichtenstein Berk.

Charles Cassell grew up during his father’s tenure as Howard’s chief architect and shared his father’s talents. The family—including future architects Alberta and Martha as well as future draftsman Albert—lived on Fairmont Street NW, a block from the university gate. According to interviews Mr. Cassell gave to Sefton and Berk in 2013, father Albert supplemented his university salary with private commissions, including the Prince Hall Masonic Temple on U Street NW, and the family enjoyed an upper-middle-class lifestyle.

After graduating from Dunbar High School, Charles Cassell entered Cornell University in 1942, but World War II interrupted his education. He left in 1944 to train with the Tuskegee Airmen, a tour of duty he later described to Washington Post reporter Alice Bonner as “in the most dangerous theater of all: southern USA,” where “his race consciousness crystallized.” After the war he completed a BA in Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1951, and began his professional career designing U.S. Navy base projects and Veterans Administration hospitals, among other public buildings.

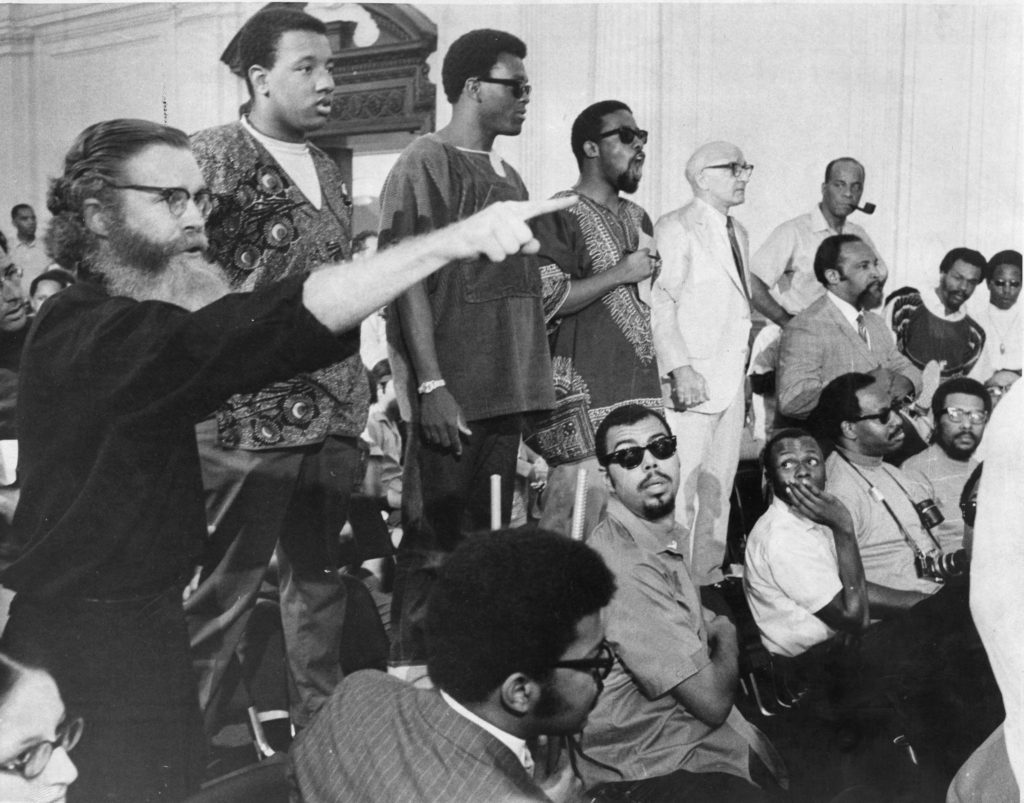

Mr. Cassell became a civil rights activist in the 1960s, joining Julius Hobson and others on numerous picket lines and protests to seek social and economic justice. Among their successes, he told the Post, were stopping the freeways threatening to erase Black neighborhoods, blocking the Three Sisters bridge, and challenging the FCC license of WMAL-TV, which led TV news operations to hire to Black reporters and anchors.

While his mainstream demeanor would contrast with the more radical styles of some movement leaders, his politics were very similar. In January 1968 he became one of the founders of DC’s Black United Front, led by Stokely Carmichael. According to Derek Musgrove’s “Black Power in Washington, D.C.” website, Carmichael hoped to bring together the city’s “large and diverse Black activist community” into a “confederation capable of seizing ‘a rightful and proportionate share in the decision making councils of the District, and rightful and proportionate control of the economic institutions in the Black community.’” Mr. Cassell agreed with this perspective, which led him to run for and win an at-large seat on the city’s first elected School Board, the jumping-off place for many of DC’s key elected officials, including Marion Barry.

Mr. Cassell was a co-founder of the Statehood Party in the early 1970s. He campaigned against freeways and in favor of building Metro. In 1982 he chaired the DC Statehood Convention, which wrote a constitution for a state of New Columbia. Although the constitution was approved that year in a city-wide referendum, it was never acted upon by Congress or the White House, which ended that chapter of the statehood quest. Mr. Cassell nonetheless championed statehood for the rest of his life. According to his Washington Post obituary, his widow Linda Wernick-Cassell said he was aware of the recent gains in the current campaign for statehood.

Mr. Cassell ran unsuccessfully for DC nonvoting delegate to the House of Representatives in 1974, charging that the incumbent Walter Fauntroy did not fight hard enough for residents. He founded the D.C. Council of Black Architects to promote equity in commissions. He oversaw the design and construction of nine buildings for the University of the District of Columbia campus in Van Ness.

Mr. Cassell also worked for historic preservation, both as a member of the DC Preservation League and chair of the city’s DC Historic Preservation Review Board. He was an advisor to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. He was a founding member of the National Coalition to Save Our Mall, a citizens group concerned with preserving and planning for the National Mall’s future. In this capacity, and as a veteran of World War II, he testified against the location chosen for the World War II memorial because it required destruction of the Rainbow Pool, a historic component of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool.

An accomplished jazz pianist, Mr. Cassell and his wife Linda founded the Charlin Jazz Society to promote jazz concerts and create memorials to jazz artists.

In 2015 the DC History Center honored Charles Cassell and his family of architects with the Making DC History Award, and produced a short biographical video as part of the presentation.

On behalf of the staff and board of the DC History Center, Trustee Chair Julie Koczela extends sincere condolences to the family of Charles Cassell.

[1] This post draws from Matt Schudel, “Charles Cassell, architect and early advocate of D.C. statehood, dies at 96,” Washington Post, May 25, 2021; Madeleine D’Angelo, “Trailblazing Architect Charles Cassell Dies at 96,” Architect, May 28, 2021; “Charles Cassell,” Legacy.com; Charles Cassell, Donald S Benjamin, et. al, “A Vision Fulfilled: a tribute to the life and work of Albert I. Cassell,” (Washington: privately printed, 1995); and Peter Sefton and Sally Lichtenstein Berk, “The Dream Dies Hard: Albert Cassell’s Calvert Town,” Washington History 27-2 (fall 2015), 3-19; Daniel Aloi, “Building on opportunity: The Cassell family of architects” Ezra: Cornell’s Quarterly Magazine 7-1 (fall 2014); George Derek Musgrove, “Black United Front“ in Black Power in Washington, D.C. website; Alice Bonner, “Fighter for Statehood,” Washington Post, March 11, 1982.