On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court delivered its landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education, ending legal segregation in America’s public schools. While this decision is referred to as Brown v. Board of Education, in reference to Linda Brown from Topeka, Kansas, it actually consolidated five individual cases. Four of them—brought by Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware—were decided on the basis that state-sanctioned school segregation (separate schools for Black and white children) violated the 14th Amendment.

But since Washington, DC isn’t a state, the 14th Amendment didn’t apply here.

It was the fifth case—Bolling v. Sharpe—that affected the students of Washington, DC. The case was filed in 1951 by Howard University law professor James Nabrit, Jr. on behalf of a group of African American parents in Anacostia and their children, including the plaintiff Spottswood Bolling. The group had petitioned for the new John Philip Sousa Junior High School (3650 Ely Pl SE) to be integrated, but the school board rejected their petition. Sousa was opened as a white-only school. Parents still attempted to get the Black students admitted to the school, only to be denied entry by the principal. (Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education)

While Brown v. Board of Education was argued on the basis that “separate but equal” was a fallacy and therefore violated the 14th Amendment, Nabrit had to take a different approach due to DC’s lack of statehood. The Court found that “racial segregation in the public schools of the District of Columbia is a denial of the due process of law guaranteed by the 5th Amendment,” (Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 500). And unlike the 14th, the 5th Amendment applies to DC.

As the editors of Washington History, our biannual publication, note in a 2004-2005 special issue, “Equal access to education and the equitable distribution of financial resources to public education have been persistent themes in Washington, D.C., since the beginning of public education in the District.” And while the Brown v Board of Education Supreme Court decision is widely known, Bolling v. Sharpe’s effect on DC, “in its special position as a combined national capital and disenfranchised local community, warrants a closer look.

This year, on the 70th anniversary of the Bolling v. Sharpe decision, we invite you to explore our 2004 special issue of Washington History magazine which commemorates the 50th anniversary. From inspiring parent activism and discouraging local dissent, to the role of Howard University in the landmark case, this issue provides important context for the Supreme Court decision. We’ve made all of the articles specially available, linked below via the JSTOR database (free registration required). You can also read a reflection from native Washingtonian and former Oyster Elementary School student Earl P. Williams, Jr. on school integration post-Bolling, available here.

-

- “The Fateful Turn toward Brown v. Board of Education,” by Clayborne Carson

- “To and from Brown v. Board of Education,” by John Hope Franklin

- “Race, Education and the District of Columbia: The Meaning and Legacy of Bolling v. Sharpe,” by Lisa A. Crooms

- “Public School Governance in the District of Columbia: A Timeline,” by Mark David Richards

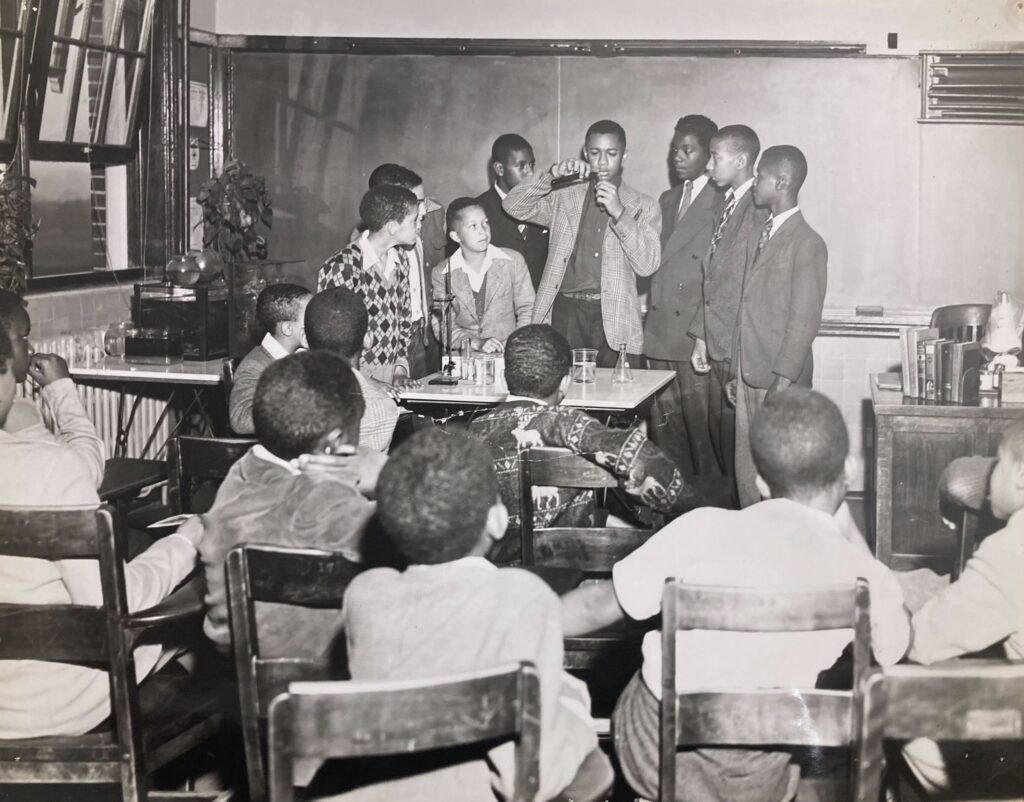

- “The Dual School System in the District of Columbia, 1862-1954: Origins, Problems, Protests,” by Donald Roe

- “‘The Showpiece of Our Nation’: Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Desegregation of the District of Columbia,” by David A. Nichols

- “‘Our Cause Is Marching on’: Parent Activism, Browne Junior High School, and the Multiple Meanings of Equality in Post-War Washington,” by Marya Annette McQuirter

- “The Role of Howard University School of Law in Brown v. Board of Education,” by Okianer Christian Dark

- “Pushback: The White Community’s Dissent from ‘Bolling,’” by Bell Clement

- “Marching toward Justice,” by Ossie Davis

- “NARA and Brown v. Board of Education, 1954,” by Walter B. Hill