The DC History Conference has, for 50 years, been a community conference. But the word “community” begs some questions. Who is in that community? Who is excluded? Who has space made for them? Who has to elbow their way in? Who doesn’t come because their needs aren’t met?

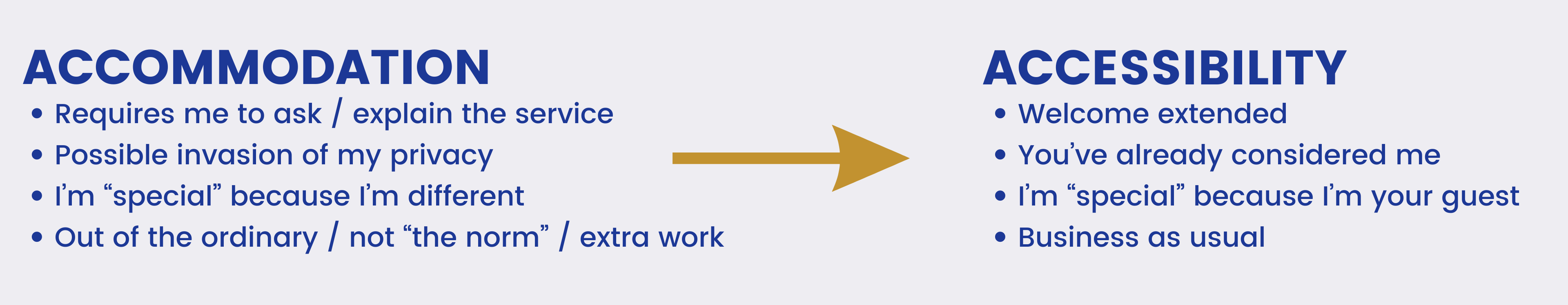

It is a problem among cultural institutions that disabled community members have to ask for accommodations to allow them to experience our offerings—programs, exhibits, etc—alongside other community members. It’s a challenge we’re facing and taking steps to solve at the DC History Center.

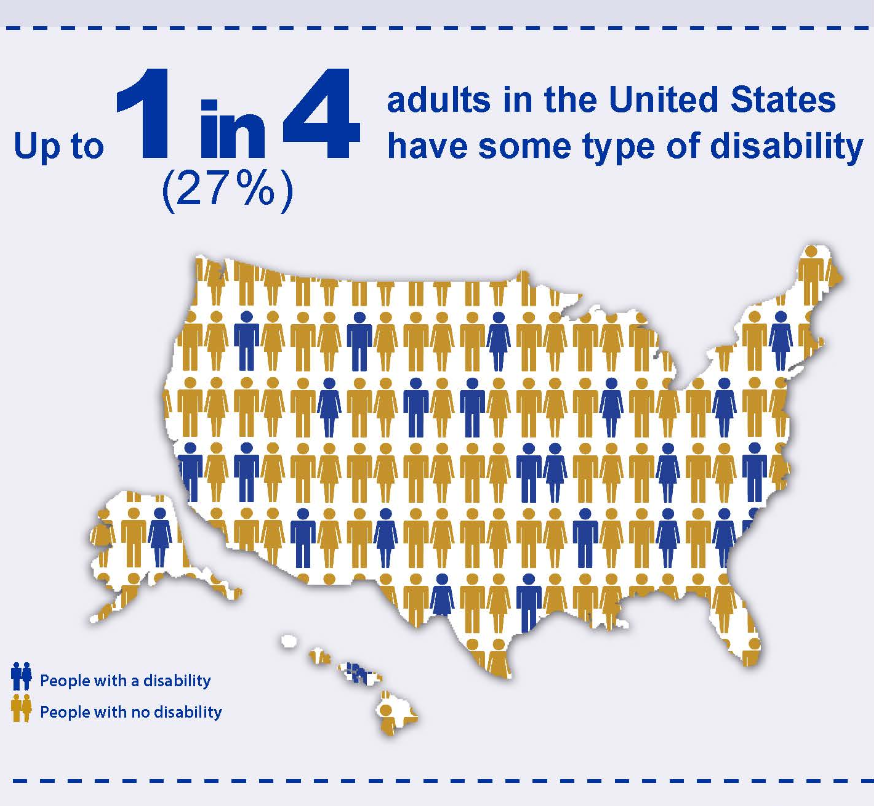

Earlier this year, the DC History Center staff listened with rapt attention at a workshop series hosted by Diane Nutting, an accessibility and inclusion consultant / practitioner. Diane challenged us to look closely at a few of our key areas: exhibits, programs, and K-12 education with an accessibility lens. When you start looking, you see things like a door handle that requires too much leverage if you’re in a wheelchair. How Eventbrite (my platform nemesis) doesn’t offer basic alternative text to make images readable by a screen reader. You hear the cacophony in Memorial Hall that could be triggering to someone with sensory sensitivities. We often don’t notice these barriers unless they affect us. (Or until they affect us: 1 in 4 of us in the United States have a disability—seen or unseen, temporary or long-term.)

But what do we do next? For me, as program manager, I needed to ask questions about how to create truly accessible programs and maybe learn from some of my peers. Luckily, the DC History Conference and our close collaboration with the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, home to the DC Public Library’s Center for Accessibility, was just the opportunity.

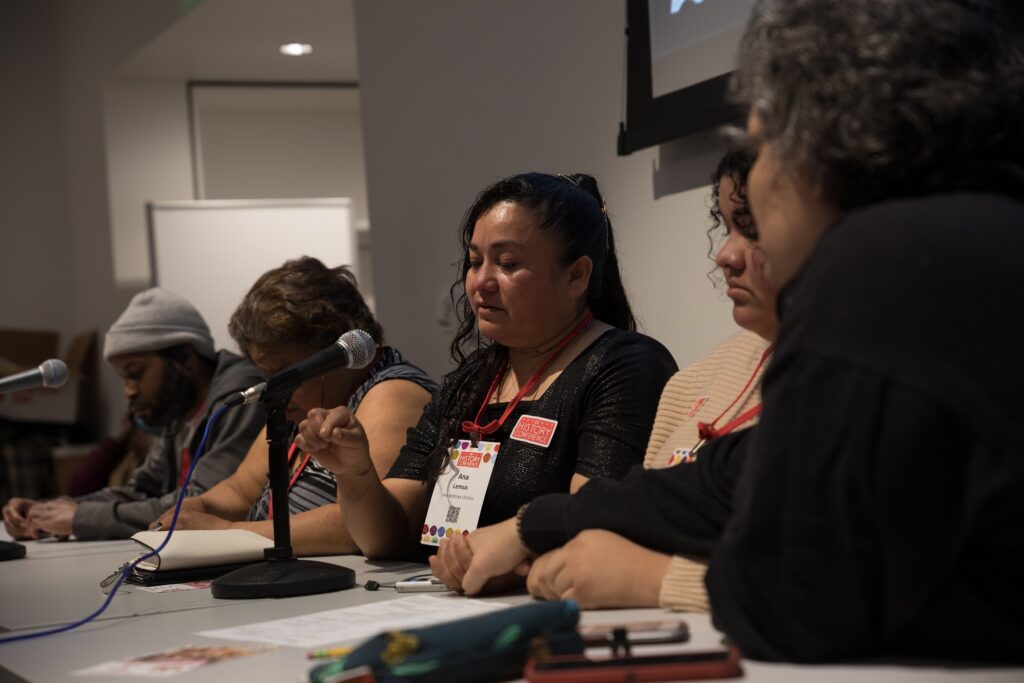

As a group, the conference planning committee agrees that creating an accessible conference is a priority. Last year, we made some significant progress: we held a free conference, provided ASL at keynotes, and minimized academic jargon. This year, during the submission review, the committee accepted a panel called “The Deaf Printers Pages: Preserving Stories of Deaf Printers at The Washington Post,” which jump started our accessibility conversation. We knew that if we’d be hosting deaf presenters and deaf attendees we would need to plan for that proactively.

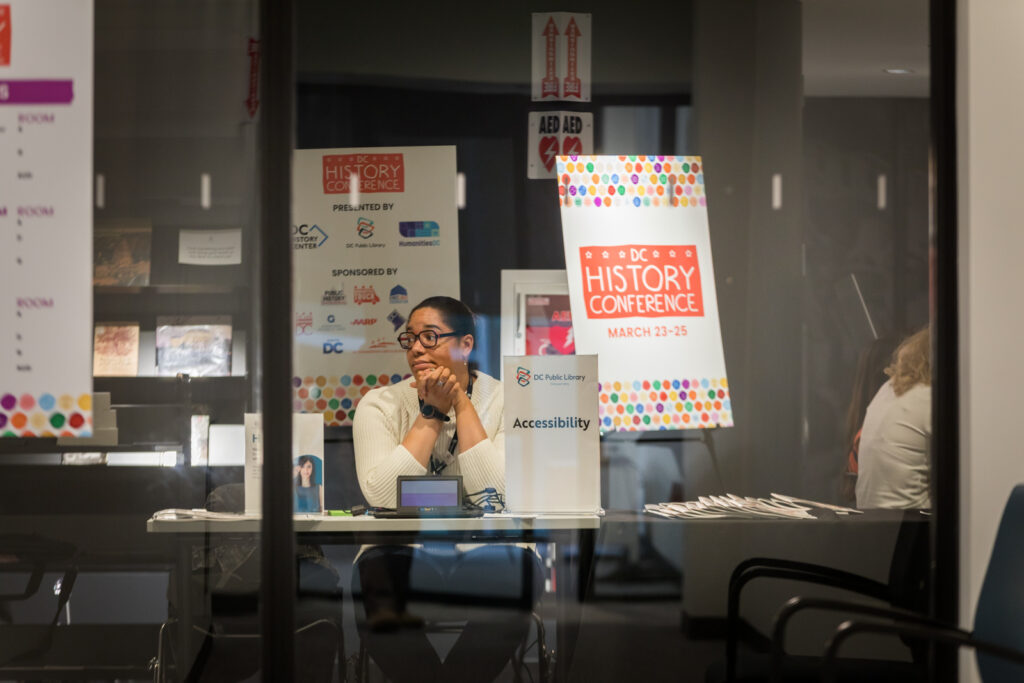

Working with Jennifer Cavallero, the manager at DCPL’s Center for Accessibility, we started a serious discussion about how to support disabled conference attendees in order to truly welcome them into the space. And importantly, how to provide support to staff and volunteers who would be welcoming all attendees.

With Jenny’s support, we agreed that all keynotes would have American Sign Language interpreters (ASL), along with CART captions projected on a screen for deaf or hard-of-hearing attendees who don’t speak ASL, and those with auditory processing difficulties who benefit from written text. For the rest of the sessions, a team of ASL interpreters would be available to join a session if a deaf participant who speaks ASL was attending. Attendees could request that in advance or on the day-of to allow for greater flexibility of access. We also agreed that the Center for Accessibility would staff a table next to the check-in and registration desk. Knowing we couldn’t anticipate every need, this provided an entry point for attendees to seek further accommodations, and on-the-spot assistance for those with accessibility questions.

Over the weekend, attendees were able to communicate via typed messages with the Center for Accessibility rep; blind and low-vision attendees were provided a braille map of the Conference Center as needed; and pocketalkers were available for sound amplification. In one case, when the ASL interpreters weren’t available for a session, Jenny arranged for tablets with Otter.ai to create live captioning in the sessions they wanted to attend. The attendees enjoyed their experience so much, they asked for Jenny’s help to download the program on their own devices.

Expanding on the definition of “access,” the DC History Conference also wanted to address language accessibility. Once the door is propped open by the question “how do we make our content more accessible to all audiences,” language accessibility is a logical companion question. Geoff Gilbert and Paola Henriquez, organizers of the panel “The Fight to Decriminalize: Street Vending in the District,” advocated for language interpretation in both Spanish and Amharic. With Geoff and Paola’s guidance, the conference was able to cover the cost of interpretation. We worked with Beloved Community Incubator’s trusted translators who provided the technology and expertise to allow the panelists to share their stories about street vending in DC in their native language. We’ve wondered how to tackle this question in our own programming, especially in our work with Latino/a/x communities. After this experience, the DC History Center is better prepared to meet that challenge.

To be honest, I considered myself ahead of the curve in the disability conversation—via my own position in the world, interest in the topic, and from growing up with a speech pathologist mother. But I was surprised by my own gaps in knowledge and how that shows up and is perpetuated in my work. As a practitioner in our field, this is unfortunately the norm. But it is an opportunity to do better, to ask questions, and specifically to create space to listen to disabled community members graciously willing to give feedback on why our spaces, programs, and practices are inaccessible. Creating accessible, welcoming spaces—beyond the language of accommodations—is essential. Thanks to the work of DCPL’s Center for Accessibility, the DC History Conference made enormous strides, strides I hope to replicate in our own in-house programming in the near future.

In the meantime, if you’d like to share your own reflections on the accessibility of DC History Center programs, my inbox is open to you at programs@dchistory.org.

Maren Orchard is the Program Manager at the DC History Center, joining the organization in 2021. As a community-oriented public historian with a focus on DC history, Maren brings a demonstrated commitment to community outreach as the basis for successful, engaging, and challenging programming. Hailing from Muncie, Indiana, Maren holds a master’s degree in public history from American University, and a BA from Ball State University, where she majored in public history and gender studies. She is proud resident of Bloomingdale.

Maren Orchard is the Program Manager at the DC History Center, joining the organization in 2021. As a community-oriented public historian with a focus on DC history, Maren brings a demonstrated commitment to community outreach as the basis for successful, engaging, and challenging programming. Hailing from Muncie, Indiana, Maren holds a master’s degree in public history from American University, and a BA from Ball State University, where she majored in public history and gender studies. She is proud resident of Bloomingdale.