A CALL TO ACTION

A few years ago during the plenary session at the 2020 DC History Conference, Dr. Melanie Adams, Director of the Anacostia Community Museum, and Dr. Izetta Autumn Mobley, at that time an ACLS Emerging Voices Fellow, discussed the role history practitioners can play in moving people towards the understanding and action necessary to create a more just future for all. Over the course of the conversation, one sentiment that Dr. Adams expressed has had a lasting impact on the way we work at the DC History Center: If you’re serious about diversifying the cultural heritage pipeline, you need to put paid internships in your operating budget.

Once in a while a colleague says something, publicly, and it shifts how you think. Perhaps this solution won’t erase the problem entirely. It might end up creating some unintended consequences. But even so, the mindset shift creates an opportunity to take a serious step forward. This wisdom ultimately led the DC History Center to include a promise to reduce our reliance on unpaid work in our Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (JEDI) statement.

As a team, we have wrestled with how to do this as a growing, but ever-lean nonprofit organization reliant on fundraising its entire budget each fiscal year. But that’s not unusual among our peers in the field, and too often the answer to so many challenges is: Let’s have an intern do it!

Internships matter. The hands-on experience they offer can be the difference between being passed over or hired for a position in the cultural heritage field. But for so many, taking an internship (when unpaid) is a privilege taking time and energy away from work that literally puts food on the table and a roof overhead. That makes internships a privilege that few can afford. So if internships remain unpaid, the pipeline to paid positions in museums, historical societies, libraries, and other like institutions will continue to remain predominantly White and upper class.

HOLDING UP A MIRROR

In a look back at internship positions held at the DC History Center from 2012 through 2020, roughly 95% of the students identified as White.

Interns from American University and The George Washington University have long been a part of the DC History Center’s networks, as have those from universities as far flung as the University of Michigan, Eastern Mennonite University, and Brigham Young University. They all received course credit from their programs, but no funding from us. Internships were not advertised on a specific schedule, but were rather the result of serendipitous timing when a student or professor reached out and a specific role at the DC History Center needed filling.

You quickly see how wealth and connections perpetuate the White supremacist practices of museum work.

STEPS WE’VE TAKEN

In a conscious shift to develop long-term relationships with additional local schools, we stopped posting open internships on our website in 2021. Instead, we have established internship pipelines with three local universities. The education manager works with a summer intern from the Public History department at Howard University. The librarian and collections manager select spring and summer candidates attending the archives program at the University of Maryland’s iSchool. And students who have participated in classes on the History of the District of Columbia and Mapping Black Land Loss at the University of the District of Columbia apply for fall internships that work on research and scholarship initiatives.

Funding for these internships is built into the operating budget far enough ahead of time that we can comfortably advertise their openings, vet candidates, and onboard them. Interns are paid even across fiscal years, regardless of the outcomes of grants we might be in the process of applying for.

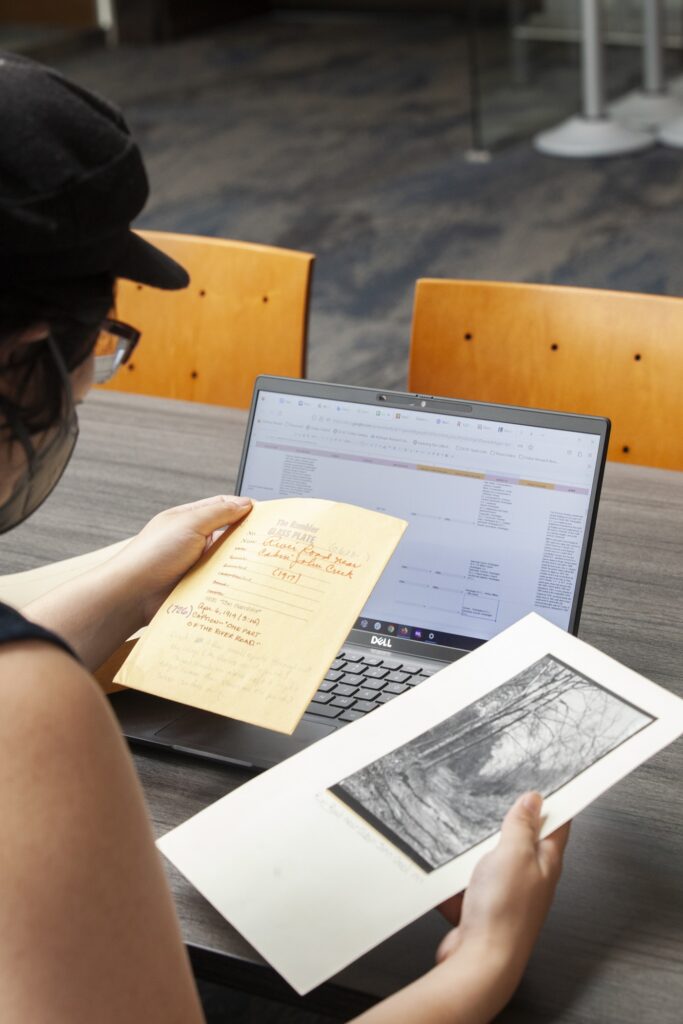

Internship descriptions now include the pay scale and payment schedule, which aligns with staff pay periods rather than a stipend distributed at the conclusion of the semester. Schedules are approximately 10 hours per week, devised with the DC History Center’s needs in mind, but are purposefully flexible to allow for the intern to prioritize classes as well as honor other professional and personal obligations. Onsite work supports professional networking, but is balanced by meaningful tasks that can be completed remotely, maximizing time and allowing for commuting costs to take up a smaller percentage of the intern’s paycheck.

There are unintended consequences to this shift that themselves need to be wrestled with: by working with specific schools, we are by default not working with others. There are now administrative tasks and roles that unpaid internships didn’t require. And funding dedicated to these internships, which are currently not underwritten, means less funding for other endeavors.

But under this system we have now had meaningful internships with six students, four of whom identify as people of color, who have all contributed tangibly to the DC History Center’s mission and received training, mentorship, and payment in return. Next in the pipeline: this fall, we’ll host our fourth intern from UDC; in the spring we’ll welcome a University of Maryland student; and in the summer we’ll have UMD and Howard students joining our ranks.

We heard Dr. Adams’s call to the profession: Pay your interns. Keep paying, and keep saying it to your colleagues. While it’s the right thing to do on an individual level, the impact goes far beyond the relationship with a specific intern. The field as a whole is better for recognizing the value of the work that cultural heritage workers contribute.

Anne McDonough is the Deputy Director of the DC History Center, joining the organization in 2012. She has served as both Collections Manager, and Library and Collections Director. As Deputy Director, her areas of responsibility include research and scholarship, adult programs, youth education, and exhibits. Anne holds a Masters in Library Science with a focus in archives from the University of Maryland, and a bachelor’s degree in International Studies/Chinese Literature, Language and Culture from Middlebury College. She is a proud resident of Adams Morgan where she lives with her husband and two children.

Anne McDonough is the Deputy Director of the DC History Center, joining the organization in 2012. She has served as both Collections Manager, and Library and Collections Director. As Deputy Director, her areas of responsibility include research and scholarship, adult programs, youth education, and exhibits. Anne holds a Masters in Library Science with a focus in archives from the University of Maryland, and a bachelor’s degree in International Studies/Chinese Literature, Language and Culture from Middlebury College. She is a proud resident of Adams Morgan where she lives with her husband and two children.